With thanks to 12355 Ian Yeates (and Maxwell Smart)

“Uh-oh, didn’t you read the instructions either”!?

This particular topic, that of artsies versus engineers, likely could have more episodes than Coronation Street, but one especially pertinent anecdote springs to mind that well illustrates the differences in the two minds. This relates to a surveying course that we had to take in Second Year at Royal Roads (1976/77). There were a number of exercises we had to complete for this course, many of which also had their amusing side, but the one I am about to relate tops my list.

Our engineering prof, one Dr. Chappelle, introduced the topic of a “transit” to the class by noting the basic requirement of establishing a position on the grounds of the college, followed by a series of observations in a circle of the angles separating various prominent points. You would add up the angles and come to, miribile dictu, 360°. As a concession to our callow and incompetent youth, we were allowed an error of 30’ of arc, or half a degree. My memory is not solid on this point – I recall 30” of arc being mentioned, which would have been, in my estimation, an impossible standard in those primitive, pre-laser days. Let’s assume the half a degree standard.

A theodolite, from back in the pre-laser days

Why you would want to do this was a mystery then and certainly remains so now. No doubt all part of the mystique of the civil engineering profession.

As usual, we were split into teams of two. My mate was Alan Stephenson, not a keen engineer per se, but not an artsy either – Alan went on to do the Oceanography degree at Royal Roads. He found it quite helpful throughout his highly successful career as a fighter pilot, but I digress. At this time, I was in progress of switching to History, my academic passion, but I had to carry on with this course for my temerity in shifting flags. No worries, happy to oblige Administration.

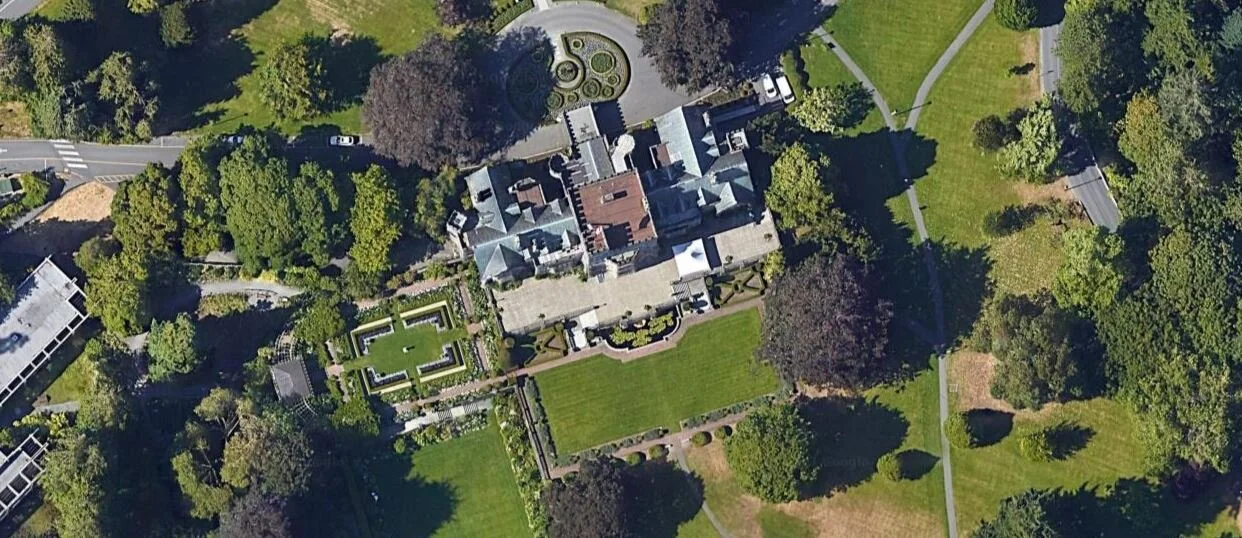

We trundled outside and found a suitable spot from where to take our observations, determined, of course, to maintain the standard that had been conceded by a generous professor. It was, I recall, a lovely fall day – sunny, no breeze – and, in short, perfect conditions to do the task. After a certain amount of mucking about with the theodolite to get it level and stable, we settled down to find our prominent points in order to start measuring. Alan and I had our little notebooks, much beloved of the engineering community, in which to record our observations. The books required a high standard of neatness and precision in forming numbers and letters as all engineers will no doubt fondly recall – it was no rough and ready record of figures jotted down on the fly. I rarely received praise for earlier exercises regarding my penmanship (‘pencilmanship’?) and so was not overly optimistic on this score but was keen to hit the mark with the assignment in terms of accuracy. I mean how hard could it be?

Alan and I selected various prominent points for the exercise and very carefully noted the bearings and jotted them down neatly and with suitable levels of precision. We even double checked the bearings that one of us had determined to confirm agreement with what the first of us had come up with. It took a bit of time to do this, but we trotted around the circle and eventually had our half-dozen measurements down that completed the exercise. I was assigned the task of adding up the observations while Alan carefully packed up the theodolite and stand, thereby demonstrating ‘concurrent’ activity and wise use of limited time so beloved of our military training to this point. When I had finished, I confess to bursting out laughing with the result. You’ll recall the objective was to be within half a degree of the 360° circle – that is, 359°30’ to 000°30’ of arc. Well, I had to confess to Alan as we returned to class, gear in hand, that our total was 349° and some additional fraction of a degree that just really didn’t matter (“Missed it by that much!”). There was no time to repeat the exercise and so had to hand in our books, quite neat as I recall, with the appalling result. I no longer recall the mark received but I suspect it was not particularly high. Perhaps we got points for effort and the neatness of our numbers and the accuracy of our addition. We certainly got no points for getting reasonably close to the standard.

Needless to add, it was episodes such as this that firmly cemented in my mind the wisdom of transferring to History. I had, and have, no sympatico for the engineering world, which is rather required to either enjoy or survive it. Naturally I remain in awe of those colleagues for whom this happy stuff was meat and potatoes. One of those ‘vive la difference’ cases. As an aside, my second career has involved working for the provincial power utility in Saskatchewan, SaskPower, which is as overly populated with engineers as the RCN. Working with them, as I did while in the RCN, has been a pleasure and simply goes to prove we need all our skills to get the job done. I bring charm and good looks to the party!